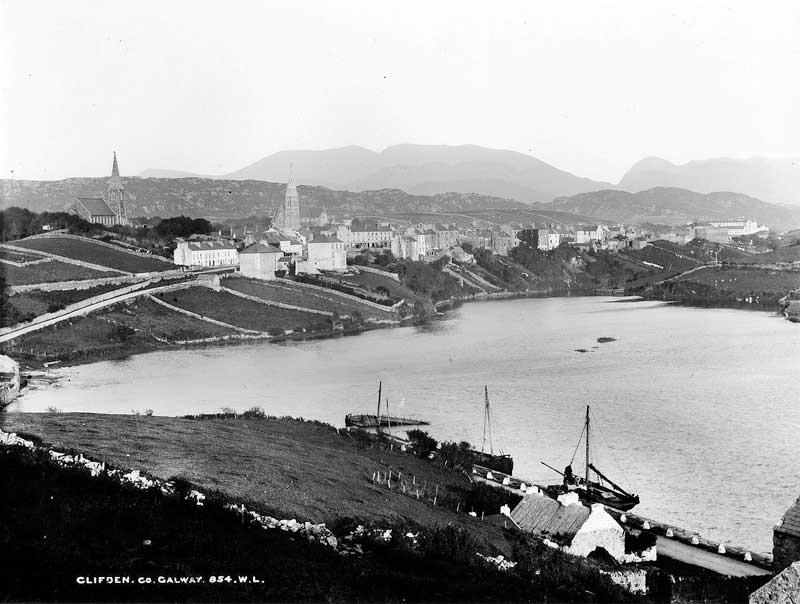

Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

By Michael Gibbons

The area of Clifden has been settled for at least 7,000 years, and possibly as far back as 10,000 years. This Age, known as the Mesolithic or middle Stone Age, was dominated by a hunter/gatherer lifestyle based on fishing, hunting of wild Boar ( the only large mammal in Ireland at the time) and fowling. Important evidence from this period came to light a number of years ago when a spearhead called a “Bann flake” was found by Jarlath Hession in top-soil he got from John Coneys’ farm in streamstown. More recently, a large kitchen midden (an ancient heap of rubbish) mostly Dogwhelk shells, was dated to between 6-7,000 years old. This midden is one of more than twenty from west Connemara and is located on the shore at Renvyle beach. This is one of only three sites dated to the Mesolithic Age on Irelands west coast. The remains of three such middens are to be found on the shores of Clifden bay, where they are dominated by oyster and periwinkle shells. Two lie opposite each other, one at the tip of faul, another at the shore at glenn Irene and a third recently discovered opposite the Clifden boathouse on the shore of Errislannann peninsula, in drinagh town land. These middens are undated and elsewhere in Connemara such middens have been dated to the bronze age 2,000 B.C. and the early christian times, 5th to the 10th century A.D. in the Errismore peninsula, south west of Clifden.

Closer to town, Velta Conneely’s keen eye discovered two beautiful polished stone axes while tending her garden on the edge of Clifden. These are very important finds and now are in the national museum and are evidence of early farming communities active in the Clifden valley between 5 and 6,000 years ago during the Neolithic or new Stone Age. These farming communities displaced the earlier hunter/gatherer and cleared the extensive mixed woodland that dominated the Connemara landscape at the time. These communities traded in stone axes and Connemara marble beads and built an extensive series of tombs throughout west and northwest Connemara. There are a number of such tombs in the environs of Clifden, but they’re extremely difficult to find. The first of these was shown to me by the late Kevin Stanley and is located at the base of a drumlin in Ardagh town land south of the town. This tomb still has its capstone intact. To the east of the town, in Couravoghil town land, the late Martin Coyne of Crocaheagla pointed out to me the remains of a beautiful tomb buried in the peat bog. Associated with the tomb are the remains of a pre bog wall, revealed by turf cutting. Similar ancient walls are to be found in the bogs between lough Auna and Shanaheever. These were shown to me by the late Nicholas Coyne. In the same area, Tom Joyce on whose land these sites were found, showed me the remains of an ancient trackway running into the lake. To the west of these, on Martin Coyne’s land, there is a small leaba agus gráinne, as these tombs are more commonly called “ag gob amach as an portach” overlooking the inner regions of Streamstown bay in letternoosh townland.

During the Bronze Age, these tombs go out of fashion around 2,000 B.C and are replaced in the landscape by less visible burials in stone cists or boxes, sometimes with a standing stone or stones above them. One of the standing stones around Clifden Castle is likely to be of Bronze Age date, the smallest one on the mound next to Henry O’Toole’s house and another possible one close to the Midden site on Faul townland, at the mouth of Clifden bay. Others occur, possibly the remains of a Stone circle, on Tom King’s land in Streamstown. In the hills northwest of the town, there is a beautiful hidden lake ”loch an Ime” and overlooking this lake, there is a long cist grave set in a low cairn. This site is covered in heather and was pointed out to me by my neighbour John Conneely and Gabriel Keady of Fakeeragh.

Another cairn of possible Bronze Age date is located in Tullyvoheen, behind one of the houses on the north side of the Clifden to Galway road. The sheltered valley, which envelopes the town of Clifden, with its rich flood plain and meandering river, would have been an attractive place to live in prehistoric times, though most of the structures were likely to have been built in timber rather than stone. Another recent discovery from the Clifden area was that of a Fulachta Fiadh (burnt mound) this site is located at the side of a small spring, on the south side of Clifden bay. It consists of a horseshoe shaped mound of burnt stone. The stones were exposed in the section face of a small path used by the horses from Errislannan manor. These sites were originally cooking sites where water was boiled in a stone or timber lined trough using baked stones from a nearby fire. Other examples of such sites are found overlooking Kingstown bay and there also found on the Island of shark, Boffin and Inislyon, off the northwest Connemara coast. The beautiful mountain valley of Gleann Glaoise, in the Maam Turk mountains, also contains a group of these sites in addition to a number of white quartz standing stones. Fulachta Fiadh generally date to around 1,000 B.C, but can be as early as 5,000 B.C.

The Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age, sometime in 6th century B.C. though this is a shadowy period in Connemara’s pre-history. A number of sites however may be dated as far back as this, including the spectacular sited Cashel (stone fort) which controls the narrow neck of land overlooking Waterloo Bridge, above Joe O’Malley’s house. The nearby sub town land of Doonen may have got its name from this site. I found this site during a flight over Connemara with my good friend Marcus Casey many years ago. Connemara has relatively few Ring Forts and those that do exist tend to be in defensive positions like this one. On the coast at Fahey, there is a related type site, a coastal promintary fort, which I used to scramble over the ramparts as a young boy to go fishing for Gunner with the Conneely’s, our neighbours, off the cliffs below. Years later, I realised that that bank and ditch was in fact the ramparts of an Iron age fort. Good view of this site from the Scardaun carpark, on the Sky road.

These sites were used up to about the tenth century, and some of them would have had “Clochán’s” or bee-hive stone built cells. The name Clifden may have derived from one such “Clochán” or perhaps a standing stone and I like to think that the standing stone which abuts the corner of the ruined St. Mary’s church may in fact be the Clochán that gave Clifden its name. There are no early Christian church sites in the town, the nearest early site is at Kill, on the Errislannan peninsula. This site is named after St. Flannan. In the current graveyard at Ardbear, there’s a beautiful holy well, Tobair Beggan. Who Beggan was, is sadly lost, though there are over ninety holy wells in Connemara, the largest concentration in the whole country. The well tradition is dominated by the ecclesiastical giants of Colmcille and Macdara. Other lovely wells are associated with Cailín, Feichín Ceannach and not forgetting the great evangelical missionary who came to us from the crumbling world of late Roman Britain, Patrick the Briton. One of the more unusual finds from here are Roman coins found in a bog in Kylemore valley in 1826. They were coins of the emperor Diocletian. The great Lakeland region between Clifden and Connemara is scattered with a wonderful series of lake dwellings, many of which were discovered in the last thirty years, and two very important ones in 2010. One of these was found on Loch Dhúleitir by Ruari O’Neill, artist, guide and photographer, North of Carna. And another very large Crannóg (island Cashel) on Ross lake, near Moycullen.

In the Ninth century, the Con Maicne mara i.e, the dog sons of the sea, were attacked by pagan Vikings from the north. These Vikings never succeeded in establishing viable settlements in Connaught, however, Festy Price of Eryephort did find the remains of a Viking burial in the sands beneath his house following a great storm in the 1940’s. Apart from his long sword, shield and dagger, there was no lasting Viking presence, as the Conn maicne mara, a war like people, saw them off. The descendants of the Vikings however, the Normans, left a more lasting legacy in the region in the form of family names and one spectacular castle, “Caislan na circe”, hens castle on the Corrib near Maam. The most common of these Norman families who were successfully Gaelicsised include the Joyce’s, the Burke’s, the Welshes, the Barry’s, the Gibbon’s, the Guy’s, the Staunton’s, the Pryce’s, The Stanley’s, the De coursey’s . However, these and the original Connemara families, the Conneely’s, the Conroy’s, the Keeley’s, the O’Malley’s etc were dominated by the O’ Flaherty lords throughout the Middle Ages from their great castles at Ard, Bunowen, Doon, Renvyle and Ballinahinch. The O’Flaherty’s of Bunowen were particularly Warlike and from their maritime base, they dominated the coastal waters of Connemara and Aran. Exported from these shores in this period was a luxurious trade item called “Ambergris”, which is derived from the vomit of a sperm whale. It was used both as a medicine and a perfume, and continued to be collected in the 18th and 19th century. During the late 16th century, the great Spanish armada, defeated in the English channel by the English and the Dutch, sailed around Britain and Ireland on their way home September-October 1588. This defeat turned into a disaster, when the autumnal storms drove dozens of these ships on to Irelands west coast, including at least two on to Connemara’s coast. The survivors of these shipwrecks were mostly murdered and or handed over to the English for execution, by the O’Flaherty’s and the O’Malley’s, a small number ransomed, while some were held over, according to English complaints, for the use of the O’Flaherty lords It is unlikely that the swarthy good looks of the Connemara people come from inter marriage with the few Spanish armada survivors who managed to survive.

The wars of the 17th century saw the destruction of the Gaelic lords, and the confiscation of their lands by the state. Some lesser lords managed to hold on into the 18th century as middlemen and traders, but Gaelic culture continued its long decline. In the 18th century however, the ancient maritime skills of the Conn Maicne mara were put to good use when they were heavily involved in a lively, if illegal, two way trade of wool, wine, sherry and tobacco. Connemara became a byword for lawlessness. This trade, together with coastal fishing, which included the hunting of Basking Sharks, brought prosperity into every Cuan, from Cashla to the Killaries. The coast of Connemara is dotted with literly hundreds of small quays, wharfs and slips, though most of these are probably to do with local trade in Turf, Kelp and Poitín, Ardbear bay is particularly rich in such features, including a very large recently discovered quay located on the south shore of Clifden Bay, opposite the Clifden Boat club. Other good examples of large quays are to be found below Morris’ house at Ballinaboy and at rusheen na cara, close to the salt lake. On inner Clifden bay, a number of very simple boat nausts have been identified, which probably pre-date the establishment of the town in the early 19th century. The trade in wool, butter, wine and tobacco was gradually stamped out, with the establishment of Clifden and the building of a whole series of Coastguard stations, the largest concentration in the country, all along the Connemara coast. The inshore fisheries of Connemara would have been of huge importance to the survival of the Connemara people over thousands of years and the continuation of that tradition is wonderfully illustrated by the surviving usage of Curraghs by the descendants of the Island communities of Inisturk and Turbot. In April 2010, a complex of fish traps was identified on a series of tidal streams that flow from Loch An Saille on the Errislannan peninsula. This ancient way of fishing, using a Cohill (net) is an extraordinary survival. The traps were used to catch Marns, a small fish identified as Sand Smelt by Dr. James King. Mr. John Folan, who showed me how these traps were used, is one of the last practisioners of this ancient form of fishing, whose ancestry can be traced back almost 10,000 years. He has since built a replica Cohill for display in the National museum in Turlough house, Co. Mayo.

By Michael Gibbons

Your article fascinated me. I’m a novelist writing about the 1580s and had the good fortune to visit Streamstown last September as part of my research. It was far too short a visit, and now I’m seeking out information about the area as my main setting in Ireland. If you could recommend any books that you think might help me, I’d be in your debt. Laura Lee Yates

There are a 3 book trilogy by Tim Robinson available on Amazon. The Coneys are my family my GGG Grandad was Samuel Coneys as it was spelt back then also spelt Connis and by the time my GG Grandmother died was spelt Belinda Conniss. I hope these books help.