Between 1910 and 1970, through various child migration schemes operated by charitable and religious institutions with government support, about 7000 young Britons came or were sent to Australia. This article sheds light on the unique case of 22 Irish boys who were displaced from a Connemara orphanage in June 1922 during the Irish civil war. They had been in the care of the (Anglican) Irish Church Mission Society and were offered refuge in Australia by the Burnside Presbyterian Orphan Homes at North Parramatta.

British child migration to Australia is a controversial chapter in this country’s history. Some child migrants have been positive about their time in institutional care, others have recalled childhoods marred by loneliness, hardship, privations and abuse. The Australian government has also been held to blame, for endorsing the separation of British juveniles from their home or in-care upbringing, however deprived it may have been. Almost all child migrants had a poverty-stricken background: many having lost one or both parents, some illegitimate or abandoned, others family runaways. Between 1910 and 1970 about 7000 young Britons came to Australia via government approved charitable and religious schemes.1 Following here is the unique case of 22 Irish ‘orphans’ brought to Australia by Burnside Presbyterian Orphan Homes in 1922.

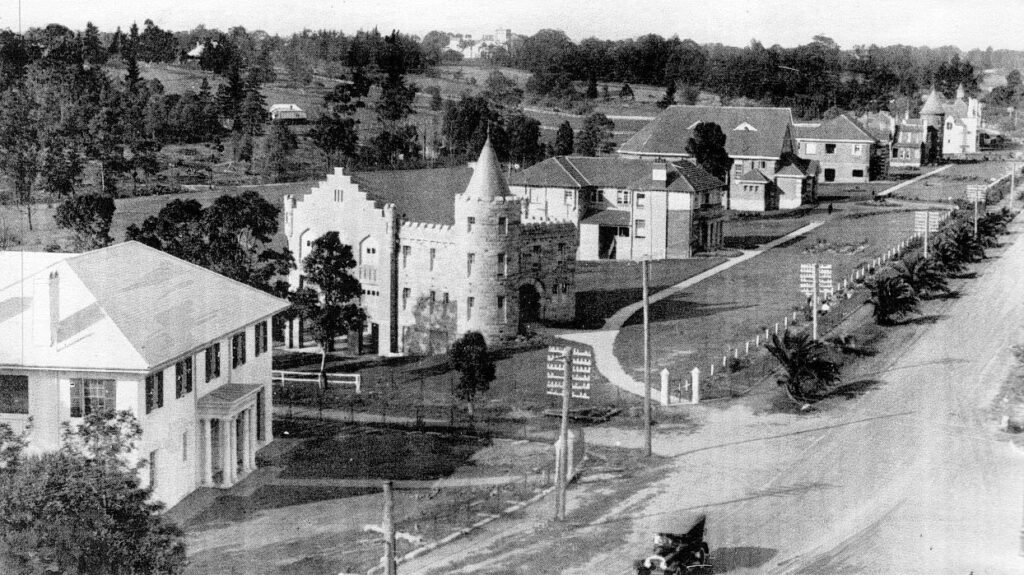

Burnside Presbyterian Homes for Children (renamed so in 1955) is today a cluster of attractive, heritage-protected buildings along both sides of Pennant Hills Road, near King’s School at North Parramatta. Although children no longer live in the homes, Uniting Care Burnside still operates from this location as one of the largest child and family welfare organizations in NSW, providing outreach programs of home and community-based assistance.

Burnside was named after its founder, Sir James Burns, a successful Scottish-born merchant who owned a large estate where the first homes opened in 1911. Burns had migrated to Brisbane as a young man, prospered from storekeeping on the Queensland goldfields and increased his fortune as co-owner of the South Pacific trading fleet Burns Philp and Co. Moving to Sydney, he built a mansion called ‘Gowan Brae’ on 200 acres at North Parramatta and became prominent in a Sydney set of wealthy Presbyterians. He turned to philanthropy after the death of his second wife, which led to the founding of a Presbyterian orphanage on 96 acres of his land. A model for its time, Burnside comprised a village of ‘family cottages’ supervised by masters and matrons whom the children could regard as parents.2

By 1922 twelve homes had opened, accommodating some 450 boys and girls, about 35 to a home. With its solid financial backing, the village and surrounding farm was a showpiece: including a beautifully designed school funded by retailer James Murdoch, an assembly hall, dairy, flower and vegetable gardens, gymnasium and swimming pool. To this point, however, there had been no policy of collecting children from overseas in the way that Fairbridge Farms and Barnardo Homes operated. Nor were children admitted exclusively Presbyterian; though in practice Protestant-Scottish traditions pervaded the institution.

(Burnside Annual Report 1923-4, State Library of NSW)

By coincidence, my father-in-law Walter Thomas was a Burnsider (1919-24) at th same time as the Irish boys. Wal’s mother died a month after giving birth to twin girls, leaving his father unable to work as a pastry cook and care for six children under 12. Two maiden aunts took over the babies, the eldest boy stayed with his father, and Wal (aged 9) and his two younger brothers were admitted to Burnside. Wal remembered Sir James Burns as a kindly old man, handing out lollies and stamps for the boys’ collections. Discipline could be strict however: the strap, and for Wal once, several days on ‘dry bread and water’ for running away with five other boys. Wal’s father visited his sons twice a month; and one year received a postcard (kept by him all his life) in Wal’s childish hand: ‘To Dad, wishing you a happy birthday from your loving sons Ellis Gordon and Walter.’3

The Irish boys’ placement in Burnside Homes was instigated by Andrew Reid, one of its board of directors. Like Burns, Reid was a successful Scottish-born businessman who had migrated to Australia as a young man. In Melbourne he had joined a fellow Scot, James Hardie, in the manufacturing firm Hardie & Sons, where he rose in status and was chosen to set up its Sydney office in 1900. Reid went on to become Hardie’s sole owner, in time making a fortune from the Australian manufacture of ‘Fibrolite’ products.4

Burns and Reid shared a view with governments of the day that Australia’s growth depended on increasing its labour force through British migration. Opportunities in Australia were being created for orphaned British children at Fairbridge Farms and Barnardos, so why not seek some ‘good Scottish stock’ for Burnside Homes? Accordingly, in 1921 Burnside’s board of directors accepted an offer from Mr and Mrs Reid to finance the building of a home for 30 or so Scottish orphans. The site was selected and architect Hardy Wilson’s plans approved just before the Reids departed on a holiday to Scotland in February 1922. As ‘Reid Home’ neared completion (at a cost of £4,836), Andrew Reid was in Edinburgh seeking some boys to fill it.5

Reid Home’s first intake – unexpectedly from Ireland

As it happened, the Reids could find no Scottish institution interested in their proposal. Then quite unexpectedly, a small notice in the London Times of 4 August 1922 presented a possible alternative. Coinciding with the outbreak of civil war in Ireland, a group of Irish orphans had been dramatically evacuated to England. Headed ‘Have you got a big empty house?’ the notice read as follows:

An Irish Orphanage has by instructions of the rebels been burned to the ground. The children after terrible experiences were rescued and are now in this country. Will someone lend a house large enough to accommodate 33 boys and staff?

– Full particulars & references from the Hon. Sec., c/- Barclays Bank, Pall Mall.

The Reids’ immediate inquiry established that the boys were from an orphanage in Connemara called Ballyconree, run by the Irish Church Mission, an Anglican society centrally administered from London and Dublin. Reid needed the Burnside board’s approval and was able to obtain this in a matter of days, as Sir James happened to be in London for medical treatment and two other directors were also in England at the time. After rapidly exchanged telegrams with Australia obtained the entire board’s endorsement, it was agreed that an offer be made to the society at the first opportunity.6

Three days later, under a prominent headline ‘Overseas Home for Irish Orphans’, the Times reported that Burnside Homes had made a generous offer. If the Irish Church Mission agreed, Burnside would cover the entire cost of the boys’ passages, housing, education and settlement in Australia, subject to their physical fitness and government approval of the plan. All formalities were settled over the next month or so, beginning with a telegram from Australia’s high commissioner in London to the Australian prime minister, William (‘Billy’) Hughes, seeking his view. Hughes replied briefly that any requisition of such children by an Australian state would need to be ‘as per agreement’- implying, it would seem, compliance with the Empire Settlement Act of 1922, a landmark step in formalising legal and financial obligations between Britain, private organizations and colonial governments, regarding migration schemes.7

In Britain, child migration was also regulated by the Custody of Children Act (1891), which gave voluntary agencies such as the Irish Church Mission the right to cater for abandoned children as they chose, no particular permission being required from a parent, relative or guardian.8 However the fact that one third of the 33 boys evacuated from Ireland did not proceed to Australia, suggests the Mission did attempt to seek this approval where it could be obtained. And so with the Mission’s agreement, and no objection from government authorities, all was clear to transfer 22 of these Irish boys into Burnside’s care.

(Robert French photo, courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Back in Connemara the orphanage was a charred ruin, never re-opened by the Irish Church Mission. The reason republicans put it to flames has a long history.9 Protestant missionary work in Connemara began in the famine years when an English Anglican, Reverend Alexander Dallas, noticed numerous destitute children during a preaching tour across the west of Ireland. This led to the organization of the Irish Church Mission Society, funded mainly by English contributors who believed that Irish Catholics streaming into England were potentially subversive, and should be converted – at home in Ireland – to the ‘one true’ Protestant faith through charity and education. This would result, they claimed, in spreading loyalty and enlightenment through the native Irish.

By 1870, the Irish Church Mission had opened 21 churches, 49 schools and 4 orphanages, mainly in Dublin, Galway and Connemara. The Mission’s initial success in gaining thousands of Catholic converts depended heavily on its free schooling and meals for children, especially in areas where Catholic schools were few and far between. Predictably, many Catholics reacted angrily to the Mission’s strident evangelism, at times assaulting staff, damaging property and scathingly branding the converts ‘soupers and jumpers’ – meaning fair weather converts who ‘jumped’ to another religion enticed by free soup.

In 1849, Reverend Dallas founded Connemara Orphans’ Nursery, near the Atlantic coast a few miles out of Clifden, the area’s main town. Clifden was a strongly pro- British town and a centre of British dominance in the district. During King Edward V11’s royal visit in 1903 there were overt displays of loyalty – including an offer that Clifden Castle could become an Irish Royal Residence should the crown elect to purchase it, and each season, townsfolk led by local gentry were hosts to an annual influx of wealthy Irish and English visitors who came to hunt and fish in the district.10 By contrast the poorest, mostly Catholic underclass barely survived through fishing or tenant farming on Connemara’s exposed and stony soil. It was from this latter group that republicans drew most recruits and support for their cause.

The orphanage by this time had two solid, imposing buildings: Ballyconree for boys and Glenowen for girls. As anti-British feeling escalated between the Easter rebellion of 1916 and the Irish War of Independence (1919-21), so too did the defiance of pro-British loyalists. In and around Clifden, it especially irked local republican activists that all the Ballyconree boys belonged to Lord Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts. The boys saluted the Union Jack at each morning’s assembly and every Sunday morning marched in uniform behind it to Clifden town centre. There were also rumours that the Ballyconree’s master and some of the older boys were spying for the crown on republican movements in the district.11

In June 1922 an Irish Republican Army order was issued to expel Ballyconree’s ‘nest of loyalists’ and destroy the home. At night on the 30th, about 25 republicans surrounded the orphanage and gave the occupants (two staff and 33 boys) ten minutes to pack what belongings they could and leave the building. All were placed under guard in a nearby chapel while the orphanage was set alight. The whole group was then marched to Glenowen Home, housed overnight, and told to leave Clifden by the first train for their own safety.12

When Whitehall was informed by telegram late that night, Secretary of State Winston Churchill ordered that a destroyer be despatched to Clifden from the British naval base at Queenstown – near Cork Harbour, instructed to advise on appropriate action. The Commanding Officer wired Churchill on 3rd July that although there was ‘no immediate danger to lives’, he had seen fit to evacuate the orphanage’s master, matron and all the boys; they were being taken to Cork and would continue on to England.13 Later that month the evacuees were in London, temporarily housed in a Barnardos Home, when the Times notice came to Andrew Reid’s attention.

Shortly after the boys were brought to England, the British navy also evacuated the girls from Glenowen. The building had not been threatened, but it was felt that the girls should be given equal protection.14 There was no move to have them brought to Australia. The next year, as elsewhere in Ireland, Connemara’s republicans laid down their arms: the Irish Free State had prevailed, with partial independence under British rule.

In November, 22 Ballyconree boys, aged 7 to 17, boarded the steamship Euripides at London. With them was Matron Emily White, their original carer in Ireland, who had stayed with them since the night of the fire. They were 3rd Class passengers, along with another 200 young men being brought out by various schemes for training as farmers. Interesting to note is that 70 of the youths aboard were ‘Dreadnought’ boys. The donors for this scheme had planned to buy a British Dreadnought battleship to assist Australia’s First World War defence, but when their collected sum of £100,000 pounds fell short for this, it was re-directed into bringing out young lads for farming.15

Living at Burnside16

The Irish boys and their matron disembarked in Sydney on Friday morning, 22 December 1922. They were officially welcomed at the Town hall and arrived at Burnside’s Sargood Hall in the afternoon, just in time for a pre-Christmas party. The Burnside Choir sang songs and carols, presents were passed out, and ‘lucky shillings’ – donated by the pupils of Murrumburrah Presbyterian Sunday School – were given to every Irish boy. Standing in for Sir James Burns, Colonel James Murdoch said that the Irish boys were now Australians and would have every opportunity through hard honest work to succeed in life, helped by their lucky shillings.17 That night, the boys settled into Reid Home – thereon called ‘Irish Home’ by the Burnside children.

Their new abode, Reid Home, was entered through a porch of big white pillars into a spacious hall. On the left was a large kitchen and straight ahead a dining room filled with wooden tables and forms. A polished wooden staircase led up to the boys’ locker room where all their belongings were kept. Next to this was the main room upstairs: a big dormitory with about forty beds and large windows fitted with roller shutters that were raised at night to circulate plenty of fresh air.

At one end of the dormitory were two large bathrooms, and at the other end the private rooms of their matrons, Emily White and Miss Taggert. Matron White had the main role in their learning. She read to them, taught them how to maintain the flower and vegetable gardens, and on weekend nature rambles, imparted her expert knowledge of edible berries and yam-like roots. Miss Taggert (succeeded later by Matron Hill) did most of the cooking, excelling with stews and the boys’ favourite sweet, peanut toffee. After tea at night it was bath time, then everyone gathered around Matron White in the dormitory to hear a bible story followed by prayers.

On Sunday evenings, everyone was rostered onto house duties for the next week. The jobs included gathering kindling for the fires; cleaning windows; polishing brass and lino floors in the matrons’ quarters; mopping the locker room, lavatories and bathrooms; scrubbing the dormitory and dining room floors; sweeping paths and raking lawns. Scrubbing the dormitory floor was a major daily task for six rostered boys. Firstly all the beds were pushed aside, then a strip of floor about six feet wide was sloshed with water. Each boy then scrubbed the full length of two boards with soap and caustic soda, followed by the fun of a running slide back to begin on the next two boards. The dining room received the same treatment.

Kitchen duties were a favourite. An early-rising older boy had to light the stove and stir up the hot water system furnace. Next, an oatmeal porridge called ‘Burgoo’ was attended to: having been soaked overnight in a large oval saucepan, it was continually stirred and sugar added as it warmed. The porridge stirrer didn’t stir too hard because the same boy scraped the pot afterwards and its burnt sugar was a treat that went with the job. There was also bread for breakfast, spread with either treacle or dripping sprinkled with salt. As at other meals, breakfast was filled with excited chatter and a clatter of plates. Then after the tables were scrubbed and all was tidied up, there was a morning prayer and the boys went off to school.

Sunday morning began with a church service conducted by Reverend Ronald Macintyre in Sargood Hall. Dr Macintyre was the first to write a history of Burnside Homes in which he recalls a visitor asking one of the Irish boys what church he belonged to; to which the boy replied, ‘I was a Christian in Oirland, but I’m a Presbyterian in Australia.’18 After church it was back to Reid Home for Sundays’ roast dinner. This was the week’s special treat: a typical meal being roast mutton and vegetables, followed by rice, tapioca or sago pudding.

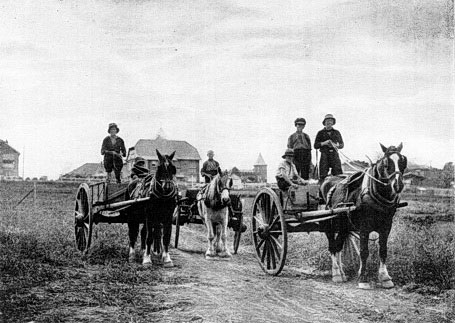

Boys 14 years and older were trained in various farm duties. These included helping to milk thirty cows, ploughing paddocks, growing corn for cattle-feed, maintaining the orchard, caring for poultry and pigs, handling horses and carts, and operating all kinds of farming equipment. The oldest boys were also responsible for maintaining Burnside’s stocks of coal. Whenever a load of coal arrived at Carlingford railway station, the boys would harness up three horse-drawn carts and drive back and forth to the various homes, loading and unloading 16 tons of coal.

Outdoor games and activities were mostly on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. Cricket, football and soccer were played, mostly in bare feet, and all kinds of inventive made-up games. Other activities included training in the gym, swimming and life-saving lessons in the pool, bushwalks and picnics, and occasionally an exciting longer trip: for example by train, bus and ferry to Taronga Zoo, or all the way to Yass for a farmstay at ‘Narrangullen’- Andrew Reid’s country property near Yass. As well, the boys could try out for the Scottish pipe band, or join the Scouts. For everyone, the monthly ‘flicks’ in Sargood Hall were a favourite event: so-called silent movies at the time, though filled with excited squeals and laughter from the enthralled viewers.

When the boys turned 16, employment was arranged for them in the outside world. First they would go with a matron to the city to be fitted out at no cost in Murdoch’s department store, courtesy of the Burnside director Colonel James Murdoch. Around the store they would go, collecting a full tweed suit, dressing gown, shirts, socks and underclothes, shoes and slippers, brush and comb, ‘housewife’ mending kit of needles and cottons, and lastly a suitcase to carry them all. A few days later, with a small sum of money, they would head off to wherever they had been appointed – mostly to farms, but in some cases to manufacturing firms, trade apprenticeships or office work.

Life after Burnside

The two oldest Irish boys left in February 1923, just two months after arriving at Burnside; followed by four more the same year. A letter one of them wrote to the superintendent was included in that year’s Annual Report:

Dear Sir,

I am very thankful for your kindness in finding me such a nice home. Mrs R — washes and mends my clothes, and also sees to my bath and bedroom. I get plenty of good food. Mrs R — says grace, and, after breakfast and tea, reads a chapter of the Bible. There is plenty of work to be done, and no growling.

I was very sorry to hear of Sir James Burns’ death. I hope soon to be able to pay a little money towards paying for my passage out. I have 13 pounds in the bank.

With kindest regards, yours respectfully,

One of the Irish Boys19

The longest any Irish boy stayed at Burnside was seven years, all having left by 1930. Most were spread out across the state, however some who were employed in Sydney kept in contact with each other the rest of their lives. Five of their daughters have provided most of the following information.

William Elliott Anderson – one of three Anderson brothers among the Irish boys – is listed on a roll of honour of former Burnside boys killed during World War 2. From his service record we learn that William was born in Belfast in 1910 and was of Catholic religion. When the War began he was married, aged 30, and living at Port Augusta, South Australia. He enlisted immediately, and a year later was in North Africa with the 2/43 Australian Infantry – the famous ‘Rats of Tobruk’, staunchly defending the port of Tobruk against German air attacks and encirclement. He was killed on 3 August 1941, during his company’s pre-dawn attack on a German perimeter post. Out of 129 Australians in the attack, 33 were killed, 73 wounded and only 23 returned unscathed.20

The Irish boy, Walter Millar, is listed in the 1911 Irish census as a two year old ‘nurse child’ in the care of an elderly (Church of Ireland) woman, living with her daughter in a one-room tenement in Dublin. He was 13 when he arrived at Burnside and left just before he turned 15. He was sent to Boxley Station near Tamworth as a farm labourer, and later worked at various properties in Queensland, sometimes shearing. In the RAF during World War 2 he contracted TB, and was in hospital recuperating when he met Olive Dillon, whom he later married. His daughter Elaine (who provided this information) was only five when Walter died in 1952, aged 43, from TB.21

A group of Irish boys who stayed close-knit friends in the Sydney area were John Longmore, Thomas Metcalf, Samuel Shaw, Albert Farrell and the three Morgan brothers, Richard, John and Godfrey. Also in touch were the Anderson brothers, William, John and Thomas. After most of these men married and raised children, they tried to find out about their upbringing in Ireland, but had mixed success.22

John Longmore and his family were unable to uncover anything about his Irish background, other than that his religion was – or became – Church of Ireland. After Burnside, he stayed close friends with Thomas Metcalf, working variously as a gardener, waterside worker and transport driver. Tom and John shared a small flat in the city as young men, and later served together in World War 2. After John married, Tom visited the Longmores often – always known to John and Doreen’s daughters as ‘Uncle’ Tom. Tom never married and died in early middle age from a heart attack. John died in 1987, aged 75. Just before he died John became a Catholic – or else reverted to his original faith.23

Albert Farrell was born in Dublin city and baptised as a baby in the Church of Ireland. His mother died when he was two and he became separated from brothers and a sister when admitted to Ballyconree orphanage. In later life he recalled the harsh conditions at Ballyconree, and that while he was there Thomas Metcalf had taught him how to read. He left Burnside at 17 to become Andrew Reid’s valet at ‘Neringah’ – the Reids’ home in Wahroonga. Albert worked most of his life for the Reid family, apart from serving in the merchant navy during World War 2. After Andrew Reid died in 1939 (pre-deceased by his wife Margaret), ‘Neringah’ became the Margaret Reid Home for Crippled Children. In 1983, after many years of searching, Albert Farrell found his sister’s whereabouts in Ireland and was joyfully reunited with her in Sydney. He died in 1999, aged 86.24

Matron Emily White, who was 46 when she arrived at Burnside, continued on at Reid Home after all the Irish boys had left. When she resigned in 1937, aged 62, the Burnside board granted her a retirement pension of £1 per week, ‘to be continued at the direction of the board’. She returned to Burnside for a few years after the War, then resigned again in 1950, aged 75.25

Some of the Irish boys used to visit Matron White fairly regularly, first at Burnside and later at her home in Targo Road, Toongabbie. Albert Farrell took his daughter Barbara to visit her there one day, photographing the little girl between Emily and Miss Taggert – a close friend since they had worked together at Reid Home. Albert’s other daughter, Margaret, recalls that her father always kept two framed photos on the dressing table in his bedroom – one of Andrew Reid, the other of Emily White.26

In retrospect, the boys were transferred from Irish care at Ballyconree to Australian care at Burnside through events and decisions of profound impact on their lives. Civil war in Ireland was conflict of the worst kind, pitching neighbours into bloodshed over bitterly held convictions. By contrast, from the time the boys disembarked at Sydney, Australia had almost two decades of peace before World War 2. At Burnside they had a healthy diet and exercise, were well educated, vocationally trained, and placed in employment. As most children do, they adapted to change, helped by being a closeknit Irish group – their substitute family. Clearly, Emily White’s motherly kindness and devoted care was an important influence on the boys’ adjustment – a supportive constant in their world, from Connemara to Parramatta.

There is little doubt the Irish boys ended up materially better off in Australia, but at the significant pain of enforced removal from their personal, social and cultural roots in Ireland. In 2009 Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologised to all former child migrants on behalf of the Australian nation – principally ‘for the absolute tragedy of childhoods lost’.27 The next year Prime Minister Gordon Brown followed suit on behalf of the United Kingdom.

Appendix: ‘Burnside Lads’, SS Euripides, Sydney, 22 December 1922 28

Alfred, Michael, 16

McNerlin, John, 14

Anderson, John, 15

Metcalfe, Ferdinand, 9

Anderson, Thomas, 10

Metcalfe, John, 11

Anderson, William, 12

Metcalfe, Thomas, 13

Dixon, William, 14

Millar, Walter, 13

Dunn, Joseph, 15

Millar, William, 10

Farrell, Albert, 10

Morgan, Godfrey, 8

Hamilton, Frank, 7

Morgan, John, 11

Lipscom, Ernest H. 17

Morgan, Richard, 13

Longmore, John, 10

Rogers, Francis H. 17

McMurray, Thomas, 10

Shaw Samuel, 10

White, Emily (Matron in charge) 46

Notes

1 Barry M Coldrey, Good British Stock: child and youth migration to Australia, National Archives of Australia [NAA], Canberra, c1999; Australia. Parliament. Senate, Lost Innocents: righting the record – report on child migration / Senate Community Affairs References Committee, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2001

2 ‘The Burnside Homes’ NZL Quarterly Magazine, vol 9, Sept. 1922, pp 25-6; Ronald G Macintyre, The Story of Burnside, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1947, pp 1-22

3 Walter Thomas, ‘Life Memories’, tape-recorded by writer, Sydney, 1984; postcard c1920, writer’s records

4 Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘James Hardie’; Reid obituary, Argus, 7 January 1939

5 ‘Reid Home’, unpub. ms, nd, Burnside Museum archives; ‘Reid Home’ www.findandconnect.gov.au/ , accessed 9 April 2021

6 Macintyre, pp 65-6

7 Prime Minister’s Dept. corres. 1921-23, A457, Z400/5, National Archives Australia [NAA]

8 Antonio Buti, ‘British Child Migration to Australia: History, Senate Inquiry and Responsibilities’, Murdoch University Journal of Law, December 2002, vol 9, no 4, part 13

9 Miriam Moffitt, Soupers and Jumpers: The Protestant Missions in Connemara 1838-1937, Nonsuch Publishing, Dublin, 2008

10 Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill, Beyond the Twelve Bens: A History of Clifden and District 1860- 1923, Connemara Girl Publications, Clifden [1986] 2006, pp 152-6

11 Moffitt to writer, 30 May 2011; Niall Meehan, letters to The Irish Times [IT], 13 January, 24 February, 2012

12 Hansard: House of Commons debates, 4 July 1922, vol 156, cc175-7; IT, 5 July 1922; SMH, 23 December 1922; Macintyre, p 66

13 House of Commons debate, 4 July 1922; IT, 27 July 1922; Hansard: House of Lords debates, 26 July 1922, vol 55, cc866-76 and 20 March 1923, vol 53, cc449-54

14 House of Lords debate, 20 March 1923

15 Boarding Officer’s Report, ‘Euripides 1922’, B4094, no 23/209, NAA; ‘Dreadnought Fund: helping boy immigrants’, Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 19 September 1922

16 G A Nilson, ‘George Arthur Nilson and The Burnside Homes 1928-32’, unpub. ms, nd, Burnside archives; Thomas,‘Life Memories’; Fred Wingrave, Burnside from the Inside, 1916- 26, ed Alice Jansen, Genial Enterprises, Sydney, 2002

17 SMH, 23 December 1922

18 Macintyre, p 67

19 Burnside Homes Parramatta, Annual Report 1923-4, Sydney

20 William Elliott Anderson, SX7495, NAA; Geoffrey Boss-Walker, Desert Sand and Jungle Green (War service of the 2/43 Infantry), Regimental Books, Hobart, 1948

21 Elaine White (née Millar), letter to IT, 18 January 2012; White to writer, 18 April 2012

22 Margaret Widders (née Farrell) and Susan Farrell, letter to IT, 5 March 2012; Widders to writer, 11 April 2012

23 Maureen Hughes (née Longmore), letter to IT, 25 February 2012; Hughes to writer, 12 April 2012

24 Susan Farrell, ‘Albert Farrell’, nd, encl., Widders to writer, 9 April 2012

25 Burnside Museum archives

26 Widders to writer, 11 April 2012; 10 April 2021

27 Transcript of PM’s address, Great Hall, Parliament House, 16 November 2009, https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/, accessed 9 April 2021

28 Boarding Officer’s Report, NAA; for ages: ‘Euripides’ (1922), NSW Unassisted Immigrant Passenger Lists, 1826-1922, www.ancestrylibrary.com.au/ , accessed 6 April 2021

Author

Keith Amos (BA, MLitt PhD) grew up in Harbord NSW and had a primary teaching career before transferring to teacher education at the University of Technology, Sydney, where he taught subjects related to Australian history. Dr Amos’s publications include the books The New Guard Movement 1931-1935, and The Fenians in Australia, 1865-1880. He retired from UTS in 2015. Keith has written widely on Sydney’s Northern Beaches history and is a regular guest speaker for Manly, Warringah and Pittwater Historical Society and similar interest groups.

This article was first published in the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 107 Part I, June 2021, under the title The Irish Boys at Burnside Homes, and reproduced here by kind permission of the author and the JRAHS.

An interesting and well researched article. Fascinating to learn what became of the boys after they were driven out of the Kingstown Orphanage on the Sky Rd, Clifden.

What a terrific read this has been.

My poor father was 7- the youngest boy. I never knew anything about his background .

Later in my life I pursued vigorously to discover his past & actually got his birth certificate but it took years to discover what actually happened to the poor boy of 7.

Very informative and brilliant read.